What does successful localisation in peacebuilding look like in practice? 9 lessons from our latest research

“I think that until now there has been a lot of imposing of agendas on local organisations … There are no spaces for communities to identify needs, priorities, dreams.”

These words capture some of the frustrations and hopes of local peacebuilders with localisation processes in peacebuilding. While many would agree with the importance of creating space within processes for communities’ hopes and needs, making this space not only a reality but a meaningful one is often challenging in our current systems.

Over the last year, International Alert and our partner Mobaderoon have been exploring how to grow this space and make localisation work in peacebuilding within the diverse realities in Rwanda, Kenya, Lebanon and Syria, with funding from the Swedish Postcode Lottery Foundation.

We talked to more than 425 people to understand what local peacebuilding actors want localisation to look like, what challenges they need to overcome to get there and how international actors, including International Alert, can better support locally led peacebuilding efforts. Those we spoke to ranged from local actors, such as representatives of civil society organisations and women’s groups, to religious leaders and business association leaders, national NGOs, international organisations and donors.

What have we identified?

Although most of those we spoke to were in favour of localisation, as we dug deeper, we realised that what different people meant by localisation varied a lot between and within contexts.

To design successful localisation processes, we need to be clear about what we mean and what the needs are.

Some participants also highlighted the risks that emerge if the process is not based on local conflict dynamics. This includes insight from Kenya that localised peacebuilding efforts can be manipulated to serve different interests or captured by elites. This was also a concern in other contexts, such as Syria, where research participants felt that civil society’s political fragmentation and dependence on external funding created a risk to its ability to meet communities’ needs. Risks are higher in active conflict contexts, like Syria and Lebanon, where peacebuilders are working across divides, often with increased risks to their safety.

However, as well as challenges, our research has also explored some of the excellent local peacebuilding that is already happening in all four contexts. This includes homegrown, traditional mechanisms in Rwanda that have become blended with official processes, active localisation mechanisms in Kenya that are engaging diverse local organisations in peacebuilding plans, transformations in collaboration between local and international actors in Lebanon and developing shared civic values across divides in Syria.

Our nine lessons learned on localisation in peacebuilding

Drawing on some of the positive examples that we saw, here are nine lessons on how localisation efforts should look in practice:

- Centred on and strengthening existing local capacities for peace. This means developing local sustainability into design and ultimately reducing the role of external actors.

- Strong and more equitable collaboration between international and local organisations. Partnerships built on shared values that leverage the respective knowledge and expertise of local and international organisations and place local organisations at the forefront of decision-making.

- Strong ethical framework for engagement. This would include commitments on common principles across civil society (local and international) that could unite organisations from different backgrounds to lay the foundations for more inclusive and positive collaboration. These ethical frameworks would be based on human rights and principles of equality, inclusion and transparency. These would also emphasise safety and safeguarding.

- Inclusive approaches that emphasise positive collaboration, dialogue, trust and active participation with a diverse range of actors, including women, young people, marginalised groups and those with different experiences and perceptions of the conflict (i.e. including across divides). This is important because of different local power dynamics and patterns of exclusion and because of different and competing interests in localisation and peacebuilding efforts.

- Flexible approaches that are adapted to different local contexts and leverage existing capacities and entry points. For example, in active conflict or crisis, such as in Lebanon and Syria, local organisations are understandably focused on immediate humanitarian needs. This means that spaces for peacebuilding are shrinking. In these contexts, entry points involve identifying opportunities for integrating conflict sensitivity and peacebuilding approaches into service delivery (such as health and social services for refugee and host communities, which build in activities to strengthen social cohesion).

- Be guided by knowledge and lived experiences of communities and explicitly recognise and address risks related to the context. This involves an in-depth understanding of the conflict dynamics, roles and interests of actors, existing peacebuilding mechanisms and current localisation efforts. This includes understanding how localisation of peacebuilding in a specific context may interact positively or negatively with other processes (such as decentralisation efforts, existing formal and informal conflict resolution mechanisms, etc.). In practice, this means a willingness to engage with risks – whilst ensuring that local actors do not hold all the risk – and engaging with diverse local actors (this can even include the spoilers), testing new approaches and learning from what does not work.

- Emphasise collaboration to overcome fragmentation and leverage impact. Building connections amongst local NGOs across conflict lines, across different sectors (e.g. civil society, religious actors, public sector, private sector etc.), across different areas and at different levels (local and national) is important to reduce siloes in peacebuilding efforts. International actors can play a role in facilitating multi-level networking to connect and scale local peacebuilding. This role should be seen as timebound and based on local priorities and context dynamics.

- Flexible programming which integrates the experiences of local peacebuilders in design and that allows for adaption to respond to changing context dynamics and needs. This includes supporting adaptive management, providing adequate resources and relevant tools for adaption (such as context monitoring) and creating space for reflection and learning.

- New, more flexible ways of funding to local peacebuilding organisations that support institutional strengthening, core funding and facilitate collaboration in consortia. Examples of funding which aim to amplify local voices and encourage mutual skills exchange include a multi-donor response to address the humanitarian and development needs of refugees and displacement-affected communities in countries neighbouring Syria. It provides technical support and more favourable funding conditions (such as low co-funding requirements for projects led by local NGOs).

Essential elements of effective localisation in peacebuilding

We have seen huge differences in how localisation processes are unfolding in these countries, how localisation in peacebuilding is perceived and being discussed, and a diversity in needs and priorities. There is no one-size-fits-all approach to localisation in peacebuilding, but the lessons that we have drawn come from examples across different contexts and will be relevant to many others as well.

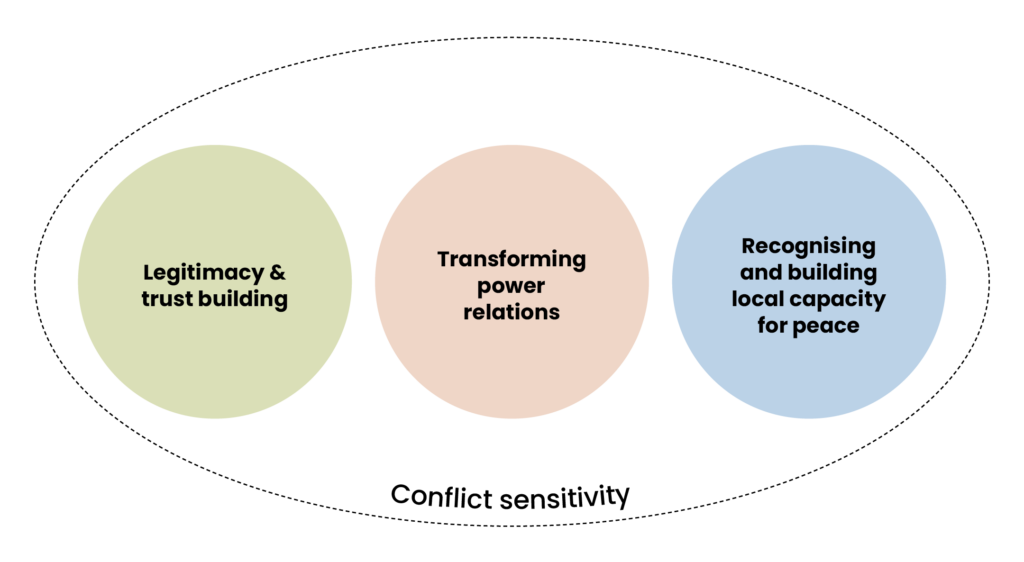

Moreover, although localisation looks different across the four countries, we have identified three broad elements common across them that can guide the design of localisation processes:

- Building trust and legitimacy between local and international actors and between local actors across conflict lines.

- Transforming power relationships between actors in the peacebuilding sector at local, national and international levels and addressing the inclusion of marginalised groups.

- Recognising and strengthening local capacities for peace through investment and tailored training that focus on areas identified by local actors. Learning should be an exchange with international actors and also learning from local experts.

Our research participants have highlighted the unique challenges related to their contexts and to localisation in peacebuilding that underline the importance of conflict-sensitive approaches. Efforts need to be informed by a strong understanding of the conflict dynamics in a specific area.

Localisation is always going to be complex, as each area has its own unique needs and differences. However, our research has found enormous energy, enthusiasm, and motivation for different organisations to collaborate, as well as some positive examples of steps in the right direction.

At International Alert, we don’t have all the answers on localisation, but we’re working with our partners and others to understand our role better. There’s a lot more to do and also a great deal that we can learn from each other, and it’s this learning which must continue to deliver peacebuilding at its best for the communities we serve.