The longest letter

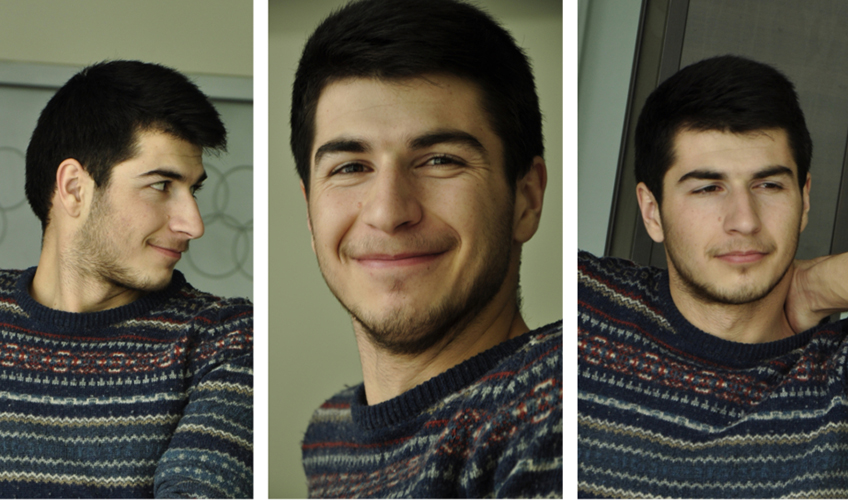

It’s me, Samir. Samir Kachayev. This letter will definitely be the longest letter I’ve ever written. I’m going to try and tell you about my life.

I was born in Shamakhi, Azerbaijan, in 1994. As my father tells it, my auntie – my father’s sister, thought it would be fun to test him. “Brother, you have another daughter.” I already had a sister, Sabina. Father replied “Well thank God – a girl! And it’s good she’s a girl – girls are children too! What’s wrong with her being a girl?” Then my auntie admitted that in actual fact he had a son, me.

My childhood

They say I was very naughty and a bit of a bully. I would take a stick and knock flowers and whole branches from trees. And then I’d get really upset when my mum would explain that trees are living things, that it hurts them and makes them cry when I hit them like that.

But more than anything I loved to throw stones. Quite a few neighbours’ windows suffered as a result. I was three years old when, after arguing with my auntie, I threw a rock at her head. It cut her forehead, which started to bleed. I suddenly got scared and started calling out for my grandma to come help her. Sabina then ran to my father, to tell him what I’d done.

Dad came home with a stick, and having told the others not to interfere, hit my hands so hard that I wouldn’t pick up a rock let alone throw one.

One time, before I started going to school, dad was doing something outside and I was hanging around irritating him. Dad gave me a slap, telling me to stop bothering him. Walking away I said “Dad, there’ll come a time, when I’ll grow up and you’ll get old.” “And, what?” he asked. “Then, you won’t be able to handle me. And you see this hammer here…” Dad replied, “then you probably understand why I hit you. I know that when you grow up I won’t be able to cope with you so I’m rushing to teach you something now.” Years passed before I really understood what my dad meant.

A serious child

At school, I was considered to be an obedient and responsible pupil. I think I learned to be responsible after seeing how much effort my father put in to prepare me for school. Months before even starting he taught me to read, write and count. My schoolteacher, Nelly Ivanovna, was a close neighbour, but she never cut me any slack.

I studied hard until the sixth or seventh grade but then somehow lost all interest. Maybe because of that girl I was always sneaking a look at. I went to school only to see her, although when we met I had no idea what to do with myself. I finished school, but I couldn’t bring myself to tell her. I was too afraid. My friend Abid was the only one who knew.

Vet, barber or sculptor?

Until I finished 9th grade, my parents worried that I would end up without a career or any prospects.

My auntie’s husband was sitting with us once and suggested I should try becoming a vet. I loved plants, animals and nature in general and agreed without hesitation. But then I failed the entrance exam by just a few marks and so my veterinary career finished before it begun, leaving my father to worry even more.

Another time, my dad’s uncle came to stay. “Nephew, what are you worrying for?” he said to my dad. “It’s not like he’s run out of career options. Send him to a barber and let him learn how to cut hair and shave. Muslims have a lot of hair, so he won’t go hungry.” My father loved the idea. He even bought me all the equipment I needed, and I started practising. It actually didn’t go too badly, and my dad became my first ‘client’.

But the search for career options didn’t end there. I was still at school and now had the option to be a barber in reserve.

Once, Father was sitting in his usual place in our garden. Not having anything else to do I was making a model of mickey mouse out of plasticine. Dad took a look and didn’t believe I’d done it all by myself. He took it apart and asked me to make another one – which I duly did. After that, dad started to pay more attention to my models. He went to Nelly Ivanovna’s son, Ilgar, for advice because he graduated from the Art Academy. He told me I had talent and should develop it.

Another planet

In our school years Sadig, Abid and I couldn’t be kept apart.

However hard it was to say goodbye to the guys, I was very excited about my future prospects. The academy was like a different planet for me. And I discovered an inner-peace I’d never known before. Within two years I had learned my craft so well I was enthusiastically sculpting as much as I could. I would arrive at the academy no later than 9am and sometimes didn’t lift my head from working until 11pm at night. When you begin sculpting, it’s hard to tear yourself away or take any breaks at all. Maybe it’s because of that I managed to finish 30 sculptures, mostly from bronze. That’s enough for an exhibition.

Students at the academy weren’t like those at other universities. We didn’t go out much, we weren’t loud in town, and if we did go out we’d meet at the new excavations by the Maiden Tower and talk. But our favourite past time was drinking tea in the workshop. Of course, it was me who brewed the tea, with thyme, carnations, or dog-rose – I know my teas.

And I made new friends. At the beginning Anar and I became friends. Not only because he was ethnically Lezgian like me, but also because we both liked peace and quiet. It was nice to spend time with Anar just in silence.

Zamik would often say “you shouldn’t be this well behaved” when in actual fact he was really well behaved himself. He had one flaw however – he refused to use bins and anything he threw away would end up on the floor. Once he bought a card with credit for his phone and threw it away on the ground. I didn’t say anything but quietly picked up the card and, seeing as there were no bins around, put it in my pocket. This seemed to have had a big effect on Zamik. “Better if you’d just sworn at me or something,” he said. After that day, he stopped littering.

I successfully passed my Bachelors, only a few marks away from the top grade. I then decided to apply to do a Masters. I didn’t tell anyone at home so they wouldn’t be disappointed if I didn’t get in. But I did and as soon as the list of successful candidates was released, I called my dad to tell him I was a Masters student. Father was so happy: “Oh you son of a bitch, why didn’t you say anything?” I told him I wanted it to be a surprise.

Surprises

Then I joined the army. The guys got me two books and I asked Mum to bring them to the swearing-in ceremony. When you’re in military service there’s almost no spare time, especially on the frontline, but I still tried to find time to read. One day our barracks were searched and my books were confiscated. I was very upset – they had been gifts after all.

At home, they knew that come March I would have a holiday and were expecting me after the 10th. But I arrived earlier and managed to surprise them. They were so happy. When it was time to go back, Mum baked me enough cakes for the whole platoon. I left on 15 March. When I was saying goodbye to my father for some reason I quoted Kochetkov: “Take forever to say goodbye, when you leave even for a moment.” My father froze and Mum worried – “why would you say that?”

Mum in general is quite superstitious. And it turned out that a year ago, when I was in my fourth year, she had a dream in which I was shot, which stressed her out a lot. Her dreams had a habit of coming true. She only told my sister. I tried to calm her down when I was leaving: “It’s just pretty poetry, there’s really no hidden meaning to it all,” I said.

I spoke with them again on 29 March when I called to thank them for the delicious cakes. I told them not to worry, that everything was ok, and military service is all routine. That day I also talked to Zamik but didn’t manage to get through to my aunt or Sabina.

In the army, my best friend was Mushvig. We would write to each other when we were sent to different positions. Recently you could feel more tension on the frontline and all units were being sent forward. Answering a letter from Mushvig from 1 April, I asked him to be careful.

That night we got the order to advance. When the fighting began, the rain of oncoming bullets made it impossible to lift your head. The last thing I saw was the commanding officer, Hasrat Almazov, getting to his feet and screaming “Forward!” and we went to attack.

Dedication

This article is dedicated to the memory of Samir Kachayev, killed in April 2016 during the so-called “Four Day War” and posthumously awarded the Medal for Bravery. This letter was written based on the recollections of his mother Atina Kachaeva, his father Ziyaddin Kachaev, his classmates Abid and Sadig and friends from the Academy Zamik and Anar.

Read more stories from other journalists in the region

- Gayane Mirzoyan, Armenia

- Albert Voskanyan, Nargorny Karabakh

About the project

Samira Ahmedbeyli, from Azerbaijan, is one of the journalists taking part in this project and wrote the above story.

Unheard Voices is part of International Alert’s work on the Nagorny Karabakh conflict. The project brings together journalists from across Armenia, Azerbaijan and Nagorny Karabakh to report on stories of ordinary people who have suffered as a result of the conflict, whose voices are not usually heard. The purpose is to ensure their voices are heard both at home, in their own societies and on the other side of the conflict divide, allowing readers to see the real faces hidden behind the images of ‘the enemy’. To view materials from all sides, challenging stereotypes and isolation.

This project is funded by the European Union as part of the European Partnership for the Peaceful Settlement of the Conflict over Nagorny Karabakh (EPNK).

The materials published on this page are the views of the journalist and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of International Alert or our donors.