Peacebuilding: now that it’s a word, let’s recognise it’s a vital policy approach

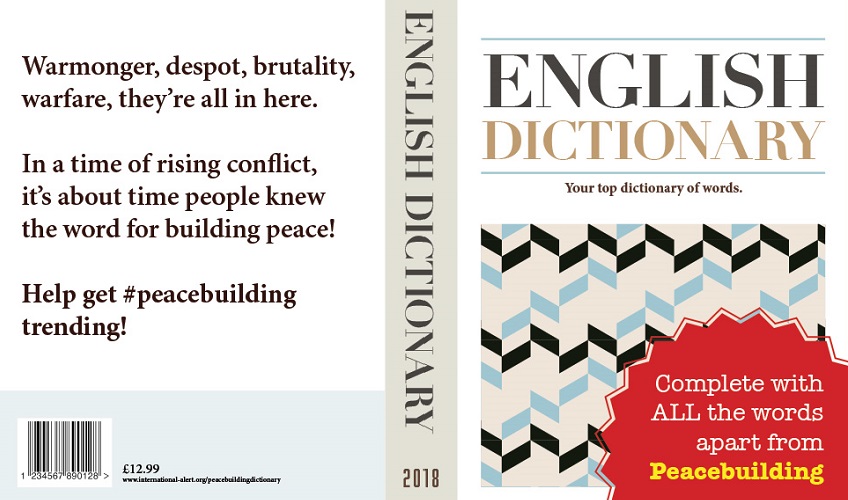

Over the past few weeks there has been a concerted effort to convince dictionaries and the software designers who maintain Microsoft Word’s spell check feature to embrace a word long used by the United Nations, nation-states, NGOs and academics: ‘peacebuilding.’

Cambridge, Macmillan, and Collins dictionaries have already risen to the challenge, placing definitions on their online versions, and other leading English dictionaries are expected to follow their lead shortly.

The issue here is not just semantic, but the belief that this approach to addressing violence and conflict is not only worthy of recognition and greater respect but is truly a vital component of successful strategies for conflict resolution.

As a former American peace mediator, I learned firsthand the essential role peacebuilding can play in reducing the likely outbreak of conflict, garnering support for prospective political settlements, and supporting scarred populations as they move gingerly toward reconciliation with the past.

No matter how effective politicians or diplomats are at the negotiating table, formal political and diplomatic actions can never be enough on their own to ensure success. Furthermore, military intervention – as we have all witnessed time and time again – while occasionally necessary, is typically a tool poorly suited to this task. Building peace needs the involvment of those people whose lives have been marred by violent conflict.

Dealing with differences before they erupt in violence, building a foundation that supports acceptance of compromise solutions, forgiving – or at minimum coming to terms with – former foes. These essential elements of conflict prevention and resolution are not primarily the province of governments, but of NGOs. These independent, flexible organisations are able to partner more effectively with local civil society actors (individuals and institutions) in ways that official actors cannot. They are not driven by the same political concerns or timelines, nor restrictions on exactly how they can engage. They also tend to be in the peacebuilding process for the long haul. By directly involving those who were affected by conflict on a personal level, such organisations help societies better anticipate and manage conflict without violence.

On 21 September, the United Nations’ designated International Day of Peace, results from an important new poll that details popular perceptions of peace and conflict will be released in New York. The Perceptions of Peace 2018, commissioned by International Alert and the British Council, and carried out by the global polling agency RIWI, asked over 100,000 people in 15 countries about how they experience and respond to violent conflict, and how they think their governments should respond. The poll’s inaugural report spotlights in particular results from Ukraine, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Lebanon, Colombia and Northern Ireland.

A clear opinion that cuts across all the nations engaged – including not only those in conflict and ones that have recently emerged – but also peaceful countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom, was about the most effective way to create long-term peace. People in 10 countries ranked ‘dealing with reasons why people fight in the first place’ as their top choice (with those polled an additional four countries ranking this factor second). ‘Supporting societies and communities to resolve conflict peacefully’ was the second leading response. These are the essential elements of peacebuilding and could be seen as part of the textbook definition.

Another key result was the almost universal view that military intervention is not the answer. It seems evident that societies on both sides of this equation recognise the general futility of this approach. As war rages on in Syria, Yemen, Afghanistan, and Iraq, there is a general recognition that fighting fire with fire only yields more fire. People polled acknowledge the need for a more thoughtful, engaging effort that emphasises caring for all affected by violence and conflict.

Even without being able to find the word in a dictionary, people understand what peacebuilding is and what a vital role it can play in helping address conflict and violence. It is now time for political leaders and policy-makers to respect the public perspective on how best to deal with the root causes of conflict. Inclusion in the dictionary is a small but vital first step in getting peacebuilding the greater political support it deserves.