Lebanese youth are reclaiming public spaces with arts and dialogue

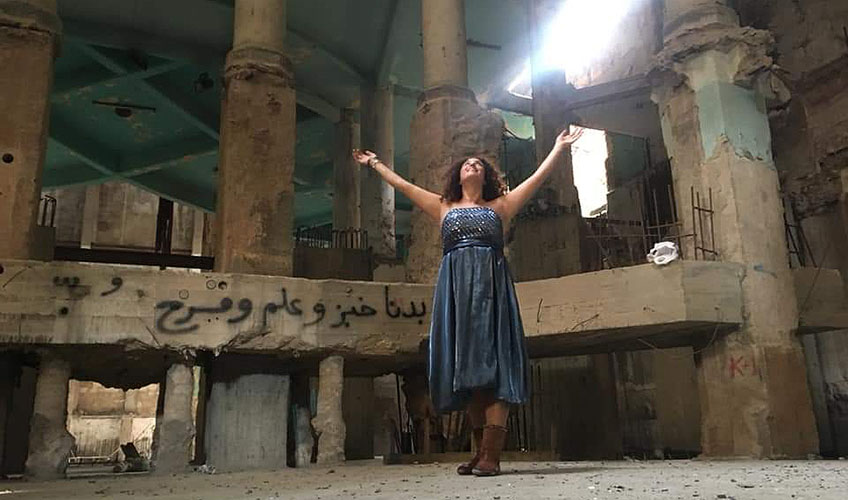

“I’ve always heard of the Opera House in Riad el Solh, and as a citizen and opera singer, it has always been upsetting for me that Lebanon is one of the very few Arab countries that doesn’t have a functional opera house,” says Hallab. “My friend and I jumped over the fence and went inside. We wanted to make a statement that some places belong to the people and should go back to the people; this is one of our legitimate rights. This is why going in there and singing, even without an audience, was a small but very meaningful victory to me.”

With hundreds of thousands of Lebanese filling the surrounding streets protesting against corruption, Hallab is one of many people who are transforming public venues into platforms and interjecting a new stream of thought stating that these venues now belong to the youth and their stories.

In a largely privatised and urbanised Beirut, public spaces remain scarce. The city’s green spaces have also shrunk over the past decades, with only Horsh Beirut being open to the public during specific times of the day. The other few open areas around downtown Beirut are designed with modern structures and remain of very little use to the average citizen. The country’s coastline, including Beirut, has been vastly privatised by beach resorts. The only remaining public beach in Beirut is under constant threat of encroachment by real estate developers, leaving people with limited access.

Ever since people took to the streets the night of 17 October, walking through the streets and alleyways of the posh downtown Beirut, one would pass by recently-drawn graffiti artwork portraying comic expressions of the political elite’s detachment from the daily struggles of the Lebanese people.

Discussion groups are being organised in Riad el Solh Square and in Samir Kassir Garden bringing together protestors from all walks of life to share opinions, perspectives and fears, and to raise awareness on the Lebanese constitution and the constitutional and legal frameworks for realising their goals of reform.

Other claims on public spaces are symbolic, with protestors blocking highways serving as arteries in and out of main cities across Lebanon – some even setting up a living room and others organising yoga classes and football games on the highway connecting Hamra to Achrafieh in an attempt to make a loud statement that they are not leaving the streets until the government resigns and a series of reforms are taken to ensure that who they see as corrupt politicians are brought to justice.

Following the resignation of Prime Minister Hariri, protestors across the country – particularly school and university students – have been galvanised to skip their classes and demonstrate. They gather in front of public institutions and arrange traditional Lebanese breakfast picnics in the privatised coastal public property in Beirut in order to “reclaim such institutions and shut down the roads to corruption,” as they chose to describe their movement.

“The house of the people” will host you for free for as long as you’d like. Bfast and morning yoga provided. Location : Ring Bridge. #إضراب_عام #لبنان_ينتفض pic.twitter.com/DYgPficAXG

— Lara Bitar (@LaraJBitar) October 28, 2019

In downtown Beirut, kiosks selling inexpensive fast food are set up in Riad el Solh and Martyr’s squares by the same youth who would, on their average days, experience such well-off areas only from afar. Some people sing, dance, smoke shisha and play cards. At night, people would climb into an old abandoned cinema known locally as ‘the Egg’, which had been closed off to the public and fallen into ruin.

What is remarkable about this uprising is the cultural and artistic dynamism of protestors promoting their own social networks and the overwhelmingly non-violent and non-confrontational approach towards security forces and pro-government citizens. Where the 2015 protests following the emergence of the garbage crisis were led by civil society activists and attracted the middle class and more educated, critiqued by detractors as elitist, this uprising has reached out across divides to socially excluded groups.

The marginalised citizens often exist in their communities under many labels, such as ‘the homeless’, ‘the drug addict’, ‘the hooligan’, but always as the outsider. With such groups reclaiming many of the public spaces through arts, culture and dialogue, they are championing their own transition into confident individuals whose voices contribute to the historical and cultural discourse of the country. Arts, culture and dialogue are successfully connecting excluded groups to the remaining constituents of the Lebanese social fabric and rebuilding the former’s self-confidence and self-esteem to reclaim public spaces that have long been abandoned or made accessible only to the social elite.

Hallab sees that arts, culture and music have always been the universal languages to express people’s desires. “Combining both passions – singing and a peaceful Lebanon – was very powerful to me. I’ve always dreamt of the day when the Lebanese people would finally unite and stand together peacefully to say that enough is enough; enough corruption, enough sectarianism, enough incompetent leadership.”

Today, community artwork and dialogue are not only functioning as tools for young people’s social inclusion and a vehicle for awareness raising and advocacy. They are also empowering them to peacefully overcome personal, societal and confessional barriers to their full participation in community life. This is being done by transforming public venues into platforms where they can voice their opinions and aspirations and make a statement that these venues also belong to them and their stories.

Such initiatives show an unprecedented level of awareness and sense of belonging and purpose by the protestors. Using peaceful methods to reclaim their communities, adopting a more critical perspective toward involvement in conflict, and enabling them to envision more peaceful ways to play a valued role in society and politics in their country.

In Lebanon, International Alert works to strengthen the resilience of local communities, political actors and institutions to conflict. We work with people from different religious and political groups to build trust, debate issues and address the concerns facing the country.

This includes supporting dialogue in the Bekaa Valley in eastern Lebanon by providing training and accompaniment on conflict mitigation and analysis to a group of community leaders and influencers. We also work with community leaders to build safer and more stable communities, and to reduce the risk of spillover effects from the conflict in Syria.